Winter 2020: determination, community, opportunities, Emily, carpe potestatum, contentment, and as always... music

<< | SolsticeLetters | >>

Dear Family and Friends:

We all realize that this season will be very different this December from what we have ever experienced before. In some respects, it will be ironically similar. Why? One of the many facets of our celebrations, whether they are sacred, secular, mixed/blended, will be with those we love and those we have befriended. Many of these gatherings will be digitally produced. Instead of exchanging gifts in person, we’ll be showing what we have mutually received in a digital form. Thanks to the amazing development of the Internet over two decades, we can be much closer to each other in ways we could not before.

My year began intensely by my trying to apply and obtain a municipal grant from The Neighbourhood Arts program. My friend, Marilyn, (a former neighbour), a visual artist and public servant, wanted to teach those on low-income in the Overbrook neighbourhood to realize their many talents –especially those of creative writing and graphic production. I had never applied for a grant before and neither had Marilyn. The experience was exciting, but also similar to discovering a totally new road hidden behind a forest, but one I longed to tread. It took two months to complete all the forms. When we submitted the whole package, we had to wait at least a month before the judges chose who would get these limited grants. We were not lucky.

I was disappointed, but I was happy to learn from experience. The other facets of this whole process taught me that there are several other ways of obtaining funding within the community. There are many other community organizations which work together to help those on low income. I plan to contact and interact with these people to obtain the support which Marilyn and I need, once this pandemic is finally over. I’ve learned that when one door closes, others open.

When the lockdowns began, I found myself writing more poetry and music. I also played the piano more often, wrote and phoned family and friends more often than I ever did before. I discovered that by writing COVID-19 letters to family, friends, colleagues, it helped me remain positive, and it has helped you also. There have been many great stories and posts on the ‘net’ which I have found inspiring, and have shared them.

I also was commissioned to compose a two to three minute work for solo violin on the pandemic. I did so for one of my colleagues. She performed it in her home and shared it around the world. There were several of us who were commissioned by her to do this, and we became universally known. It is astounding what huge crises in our lives can create! It is ironic that something so horrible and deadly can propel a few creations which can be uplifting.

This is a reply I sent to a Facebookpost re: post –pandemic planning:

To go forward from my perspective means educating our offspring and one another to affirm and celebrate the uniqueness, as well as the many similarities of each and every human being. It also means adopting Nature as not something outside of us, but fused within us. To do this, we must learn to accept ourselves and then to learn to have patience with those 'others' whom we cannot easily understand. We must rid our societies of the unneeded competition. This competitiveness began many centuries ago. In our lives, it has begun before we even entered school. Most of it is needless. It exiles many children and youth from being accepted. We must create community councils and committees to embrace those from the working class, low-income, middle, small business, upper class, professionals, clergy, educators , artists of all kinds and more. Each representative at the table must have equal time to speak to any and all issues and their comments must be recorded and saved just as they presented them. This is just the beginning....

***

Diane Schmolka left a reason for downloading A_metaphor_is_a_metaphor

Dear Arlene Tucker:

I am a musician, poet, writer, animal lover, and continual seeker of knowledge of all kinds. An analytical paper like this is intriguing. Thank you for posting this.

Diane Stevenson Schmolka. Jun 19

This pandemic has been much described. It will be remembered as not only an iconic event in our Earth's history, but is quickly and quietly becoming thought of in similes, metaphors, allusions and allegories. Because it has affected each person on this Earth in many diverse ways, the memories will create stories, new customs, traditions and new 'vocabularies'. Some of these similes, and metaphors will be visual, some-auditory, some odorous, some gustatory, some kinaesthetic, and some will be fused with all of the above. I believe even our humour will be stretched into new forms. It might just begin with "a metaphor walked into a bar and met a beautiful simile, which became their umbrella for their rainy days"...

(That is the most concise I can get. There is a creative writing contest on the net for writers to write a novel in six words or less. Most of you know me well—go figure...)

***

Below is an event which changed Emily Dickinson’s Life. Thanks to this event, we now know not only her poetry, but her ways of thinking and what her life values and ethics were. Her poetry has taught me much.

The Letter That Changed Emily Dickinson’s Life

At a Crossroads, She Sought Another Writer's Counsel

May 26, 2020

On April 15, 1862, Emily Dickinson did not set out to write the most important letter in American literary history. But many scholars believe that's exactly what she did.

In Amherst, Massachusetts—with schooling behind her and seclusion setting in—Dickinson was at a crossroads. Already she had been seriously writing poems. She had taken to assembling small booklets of her verse: writing 20 or so poems onto folded stationery, stacking each folded sheet one on top of the other, and then stitching up the sides. "Fascicles," an editor later called them.

With over 400 poems written, some of them shared with friends and family, and a few published anonymously in newspapers, 31-year-old Dickinson wondered if she were ready to go public—or at least ready to reach out to a stranger who might know how to direct her.

A recent article in the Atlantic Monthly had caught her eye. "Letter to a Young Contributor" by essayist Thomas Wentworth Higginson offered advice to would-be writers who sought publication. Higginson's suggestions ran the gamut from the practical (use good pens, black ink, and white paper) to the profound ("There may be years of crowded passion in a word, and half a life in a sentence."). Although she rarely corresponded with someone she did not know, something in Dickinson moved her to respond.

Weeks before, Amherst had suffered a terrible blow. Frazar Stearns, the beloved son of the Amherst College president, had been killed in battle. Dickinson watched her brother keening with grief. He keeps saying, "'Frazer [sic] is killed' – 'Frazer is killed,' just as Father told it – to Him. Two or three words of lead – that dropped so deep, they keep weighing." One of Frazar's college classmates built a coffin out of discarded wood from the battlefield and rowed six miles down the Neuse River to Union gunboats offshore. He stayed with Frazar's body until it reached Amherst, where William Augustus Stearns could not bear to view his 21-year-old son's body.

Emily Dickinson didn’t ask if her verse was "publishable" or "good." She knew all along, didn't she?

The Union victory in New Bern, North Carolina in March 1862 had been a decisive one for the Amherst Boys, a regiment led by former chemistry professor William Clark. After troops that day captured a Confederate cannon, Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside directed it to be sent to Amherst to acknowledge the sacrifice of Stearns and others. Later the college held a ceremony dedicating the cannon, and the poet’s father offered remarks. In his address, Edward Dickinson noted that all lives are touched by the sweep of history. In this precipitous moment, he said, individuals are tied to the events surrounding them by "sacred associations."

The next day, spring was stirring. In his daily weather journal, Amherst College professor Ebenezer Snell recorded that ground frost had finally thawed. Cirrus clouds scoured the sky, and—in the vernal pools around the village—trees frogs were beginning their seasonal chorus. Never had Emily felt more ready to share her work with the world. Perhaps her father’s words about "sacred associations" propelled her. Maybe she realized that readers she had counted on—her cousins, sister-in-law, and friends—were busy with their own lives and not as available to her as they once were. Mounting war deaths and her always-intense awareness that life could change in an instant galvanized her. Patriotism might have played a role too. "This American literature of ours will be just as classic a thing, if we do our part," Higginson had written in the Atlantic, "If, therefore, duty and opportunity call, count it a privilege to obtain your share."

Dickinson sifted through her poems, and selected four: "We Play at Paste," "I’ll tell you how the Sun rose," "The nearest Dream recedes – unrealized," and "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers." She took out another sheet of paper and wrote.

Mr. Higginson,

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

The Mind is so near itself – it cannot see, distinctly – and I have none to ask –

Should you think it breathed – and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick gratitude –

If I make the mistake – that you dared to tell me – would give me sincere honor – toward you –

I enclose my name – asking you, if you please – Sir – to tell me what is true?

That you will not betray me – it is needless to ask – since Honors is it’s [sic] own pawn –

When Thomas Wentworth Higginson collected his mail from the Worcester, Massachusetts post office, he pulled out a letter with a curious scrawl. The letter bore no signature, but inside was a smaller envelope, and written on the card was Dickinson’s name. He read the poems, and wrote back immediately. It would be another eight years until Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Emily Dickinson met face-to-face, but the relationship begun with that portentous letter would change their lives.

Higginson learned quickly it was best not to offer Dickinson advice. She knew her mind better than anyone. But what he could not offer in critique, he offered in constancy, friendship, and an enduring interest in the wild terrain of her mind. When she died in 1886, he traveled to Amherst to read an Emily Brontë poem at her funeral. Later, after Dickinson’s sister found sheet upon sheet of poems tucked into a dresser drawer, she contacted him. Higginson and co-editor Mabel Loomis Todd went to work, and in 1890, Emily Dickinson’s Poems launched into the world.

For the rest of his life, Higginson continued to think about that first letter with its eruptive first line, trail of dashes, halting syntax, and envelope-in-an-envelope. But it may have been that word "alive" in the first sentence that never let him go.

When fate threw the two New Englanders together on April 15, 1862, Emily Dickinson didn’t ask if her verse was "publishable" or "good." She knew all along, didn’t she? She understood poetry had to transport, had to be visceral, and had to find its way into our bodies. On that soft spring day, Emily Dickinson took the most unprecedented step of her life. Her letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson altered the course of American literature, and taught us that great poems must breathe. To hit the mark she wanted, Dickinson knew poetry had to be consciousness itself, and alive with possibility.

Brownian Motion (a found poem)

it all begins with pedesis when there was just dust and miniscule molecules of gas darting in all directions at many different speeds longing to find a place yearning for fusion needs enclosed spaces such high heat in new places creates new relocations love has its own rules and regulations in the beginning with no chosen direction thermal equilibrium combines linear and angular momentum without aforethought becomes instinctive hormonic motion and becomes dull and null over time conception is each pollen moved by water

It might be only tears or tares a swamp a salt lake or a shower after a forest fire but creation does not govern probability love’s interactions are gradual processes an imperishable seed of dynamic equilibrium death and rebirth one and the same expression of collision conception collusion leaping dust

© Diane Stevenson Schmolka

This Found Poem is based on Brownian Motion.

- { Brownian motion, also called Brownian movement, any of various physical phenomena in which some quantity is constantly undergoing small, random fluctuations. It was named for the Scottish botanist Robert Brown, the first to study such fluctuations (1827).}

Clowns At Night Rarely do we sleep now, when stars are out there in vast palpating universes images memories and nightmares provide three dimensional canvasses to amass what we creators learned from childhood experience Our instruments hidden and silent by day spring a wake in the dark, warp and weave molecules and chromosomes fused in exploding colonies in which our synapses spark together while human life drowns in sinkholes of human tissue we are clowns at night invisible in daylight like fireflies and nightingales tigers and singers we now grope together on new unforeseen paths to search for redemption to forgive our ego-centricity finally we will have been given a new stage the canvas and manuscript will be sci-fi non-fiction we will not have a choice between narcissistic entertainment our productions will be team creations but we’ll be able to retire from the night circus of plastic imagery stunts and propaganda what is the meaning of safety might it possibly become new dawns of unconditional trust? © Diane Stevenson Schmolka. First Draft, inspired by M.Chagall’s “Clowns at Night”, 1957.

I was just reading a report about technology of cochlear implants . The report was called 'Understanding Hearing'. They described 'functional hearing' as being dependant on interaction and body language of the mother.

I had, about 10 years ago, a deaf-mute student. She was in primary school. I began to realize that she was hearing 'sub-text' much better than children and adults who were much older and not deaf.

Although this report is a well-researched one, I think some of these scientists and technical researchers, have missed the point.

Children, whether born deaf-mute, or 'normal' when they’ve been shown empathy from the beginning, by family members. It is not 'understanding hearing', it is ‘hearing understanding.' That is what empathy really is: hearing understanding on a non-verbal level. It is silent, and, for me, the beginning of creative output.

It is what develops, for me, what was thought of in past centuries, the 'soul'.

That student taught me so much. She completed her training as a chef, recently, but is now taking courses in creative computer – artistic design.

(A diary note written Dec.7,2013).

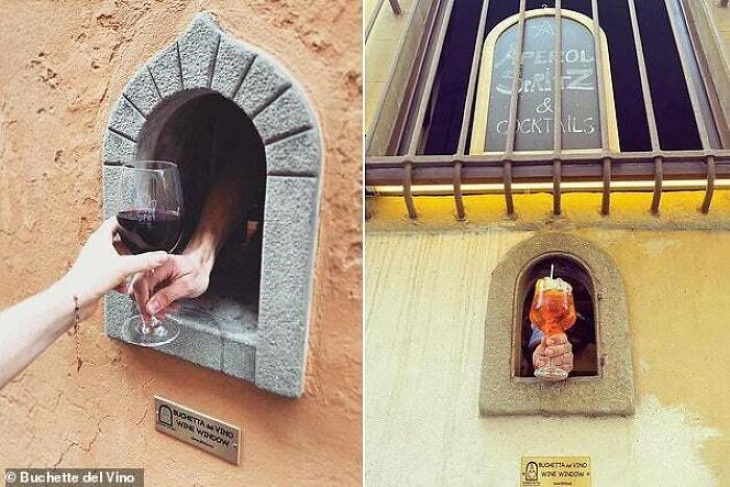

"These so-called wine windows were used by vintners in Italy to sell wine during plague pandemics in the 17th century. Now they are coming back to use due to coronavirus."

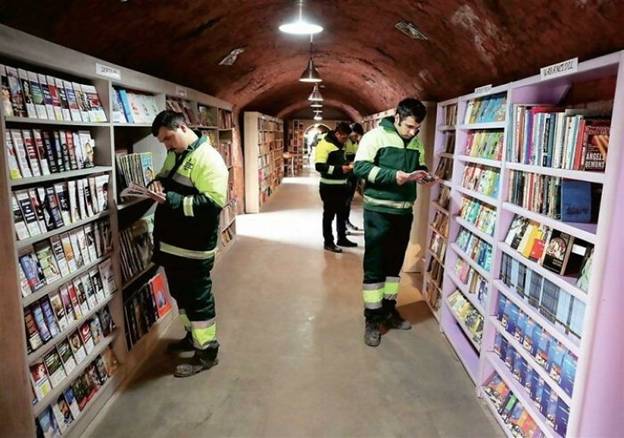

Turkish Garbage Collectors create Library with all books people have thrown into their trash.

Today is December 7th. It is late afternoon. The darkness will fall just before Peter and I will have our usual early supper. I don’t make ‘dinners’ much anymore. We eat simply. Miko, our short-haired tabby accompanies us for a short time, then proceeds to our bedroom to take his early evening sleep. After I’ve cleaned up the dishes and pots, we proceed to our computers or I read a book. I’ve tried to summarize concisely what this past year of my life has meant for me. I cannot pin it down neatly. Last year at this time, I was still having physio-therapy from my April 5th femur and ball-and-socket joint fractures, trying to plan for a quiet, but sociable Solstice season, writing my Solstice Letter, still trying to de-clutter the den from bins still un-packed from that year’s (2018) move from Shelley Ave.. Two months after that, COVID-19 became serious; then early March produced the ‘Lockdown’. Yes, I found solace in creative writing: poetry, composing music, reaching out to others. No matter how much I tried to avoid the reality of this pandemic, I began to realize that I must think ‘forward’ about my communities: those in this Francesca Complex, the Overbrook neighbourhood in which Peter and I live, my relatives, friends, the two salon music clubs to which I belong, my Unitarianism, my total love of nature in all its forms.

While I have been advocating much more collaboration for artists of all kinds, I’ve always composed singularly, and have enjoyed my aloneness in that manner of creation. Isolation though, creates mental ‘walls’ which barricades more adventurous creative output. Artists are known as ‘community builders’. We’re like the ‘pro-biotics’ of the guts of a successfully completed community. I now have realized that artists of all kinds and genres must learn very soon to create together new ways of creating works of art in new ways. If Emily Dickinson had not written to T.W. Higginson, she would not have been able to be published. She needed feedback from a professional writer.

We have to approach creating and composing in a similar process as do chefs, chemists, archeologists search and research to find the hidden ‘clues’ of lost or rare items and thus find new ways of learning how to learn. Each creation is not an end to a work; it is the petiole of the leaf, the force of the muscles in female animals which births the egg or babies out from wombs, the lip of the pond, the marshes and swamps. At times when we feel we have nothing left and cannot find our creativity, the ‘dessert’ we believe we’re in becomes the creative sand which propels us up and out. We can create our own spring of fresh water by reaching out and creating together.

The photo of the Turkish Garbage Collectors’ library describes how working ‘forward’ together builds communities. I wrote the two poems I’ve shared after realizing that by having to meet my groups by ZOOM, I’ve been learning how to create communally. Last evening, I participated in our Musical Arts Club Christmas Meeting. It was lovely. Not every member could attend, but we shared many stories, feelings, humour. We listened with our hearts. I found it very creative. Tomorrow evening, I will be with my Harmelodic Club by Zoom. We’ll be sharing stories, singing carols, listening to some new Canadian composed carols and songs. We’ll be creating memories. These are the real ‘gifts’ from my perspective. Friendships are priceless gifts. Our families are our anchors in life and our friends are our boats which carry us up and down all the rivers of our lives.

You have all helped to make my life very creative. I wish you all a very meaningful Solstice Season and a very joyful New Year.

Love,

Diane.

<< | SolsticeLetters | >>

Page last modified on December 25, 2020, at 07:16 AM